The sight of that yellow-and-blue Big Top meant that the five-year old Cirque du Soleil was back in town again. For me it brought back my fondest childhood desire: to run away and join the circus, just like Toby Tyler did in a favorite childhood book..

By the time I had read the strangely spiritual yet earthier “Circus of Dr. Lao” by Charles G. Finney…

enough years had passed that I knew it was impossible to escape all the problematics of my childhood. And to try and accept that I would never meet the baby flying elephant known as Dumbo, nor even see Jimmy Durante, the clown in “Jumbo.”

But at least I could go and meet the people who had left their normal lives and joined up with this Cirque. A piece of paper typed in French graciously gave me permission for backstage visits before the show’s opening date. I held this carte blanche to Le Cirque Reinventé before me. With no animal acts, it is indeed a reinvention.

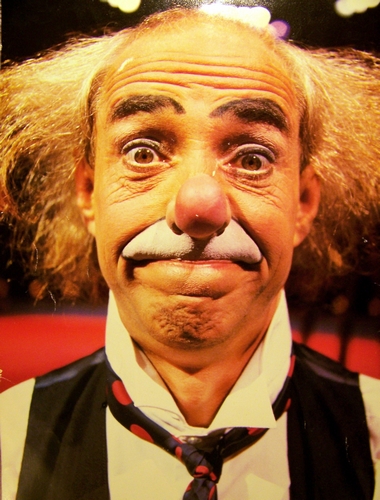

First, of course, I wanted to talk to the clowns, and the funnyman anchoring this year’s tour to San Francisco is Benny Legrand. He comes on even before the show commences, berating members of the audience as they are finding their seats. “The show is over-rated,” he announces, “you paid too much for your tickets. You might as well go home.”

But actually he wasn’t sad that an opening night benefit netted $30,000 for San Francisco’s financially-troubled Pickle Family Circus, the original circus home to master clowns Bill Irwin, Geoff Hoyle and Larry Pisoni (“Lorenzo Pickle”).

In visits past, the Canadian company had raised hefty sums for the homeless and for AIDS causes. “Gay issues are not superficial or just campy anymore,” the out-of-makeup clown told me, in his flat Saskatoon twang. “From gay bashing to [Senator] Jesse Helms’ art censorship, we’re dealing with a conservative swing abetted by some medical emphasis, and it is dangerous. People are going to have to get more militant.”

Benny’s creator and alter ego Wayne Hronek has been known to Act Up himself. In one city where AT&T signed on as a corporate sponsor, Benny faxed a letter of complaint back to headquarters in Montreal and got a meeting with phone company muckety-mucks to grill them on their South Africa investment policies. And once, right in the middle of a performance when his own contract was slow in getting signed, he sat down in the middle of the ring to announce this fact to all the circus-goers. Audiences love his out-and-out honesty, his anti-sociality. Clowns have always been the wild card in the cast, and in general “the circus traditionally collects employees that are uncomfortable in straight society” he explains.

“I run counterpoint to whatever the circus does, no matter how syrupy or saccharine it may get—or if it becomes too commercial. The Cirque du Soleil is a lean green machine, and it needs to have rough edges put on it.” As a stand-in for all the hostile feelings people are not supposed to show, Wayne sees himself working the honorable Native American tradition of the “contrary,” like the Crow warriors who rode into battle backwards on their horses to show disregard for death, or the Zunis who turned even their most sacred ceremony upside down, he informed me. “Then there was the court jester who offended the king and was banished to France and told he would be beheaded if he ever again set foot on English soil. But after a year he returned from the Continent. When confronted he took his shoes off and inside was French dirt. For that episode he was given a pardon.”

Benny’s influences are also modern. “My role models were on TV—the Three Stooges, Amos ‘n Andy, Abbot and Costello—though we didn’t have a television until 1952. My mother was still hauling water from the well and heating it on the wood stove. My grandparents were gypsies from Bohemia; once in Kansas my grandfather wound up working as a sharpshooter in a Wild West Show. And I’m not making this up. Joseph and Mary Hronek rode a covered wagon into Alberta, Saskatchewan.

“And Aunt Helen got kicked out of one of those private old-folks’ homes for running a craps game. When we took a bus and arrived in Vancouver for my uncle’s funeral, she turned around, this fat grandmotherly lady, and said to me in a loud voice: ‘Young man, would you get your hands off my buttocks!’ My aunt was an inspiration.”

Benny has been seen grabbing an audience member’s purse and pulling a plastic bag of white powder out of it. Early in his act he “borrows” one circus-goer’s tie to wear during the sloppiest possible paint fight. Then while cleaning up, audience members get hosed down too. “Anti-social action, when you add laughter, can become acceptable,” Wayne avers. “Pretentious attitudes can drop to the point of becoming fun. And after all, it is only water, what you drink, what rains on you. And someone wearing a tie to the circus! Where do they think they are going? It isn’t exactly Aida.”

In the ring Benny Legrand uses a minimalist version of traditional clown face, with white makeup on his upper lip only. “It still provides the frame of reference, like security blankets for people who need them to hang onto.” He still utilizes a red nose “and my hair stuck straight out with some ozone-friendly hairspray.” But his hair looks lavender-colored in performance. “That’s all done with backlighting. You should talk to Luc Lafortune, our lighting designer,” he offers when sending me deeper backstage.

I found Luc in the circus’s French-style chow-line (on menu that day was Toast aux crevette du crab). Like many I met behind the scenes, Luc seemed to lead two lives. Along with a BFA in Theater Arts, he had studied psychology at McGill University in Montreal (“Sadly, they still taught behavioralism”) and was instrumental in giving the Cirque du Soleil its colorful New Age-cum-MTV post-modern look.

Another key mover the audience never sees is Rachel Sauve, because during performances she is dressed all in black inside a black tule-cloth “box” that forms the artists’ entrance to the ring. This is one of the key places where techs work with television monitors and earphones to coordinate sound, lighting and special effects. “And I,” she tells me with no small amount of pride,” am the first and only woman on the technical crew. I used to be a gymnast and an aerialiste so I was pretty strong. Still, it took me a while to make my place on the crew.” She also drives the 33-foot campers and the “BMs”, smaller vehicles that convert into sleeping cribs for staff and performers. “Everyone calls them BMs, passion wagons, from the word baise—to have sex. Any time we make love, the whole truck shakes.” Her living space is about 2.5 yards square.

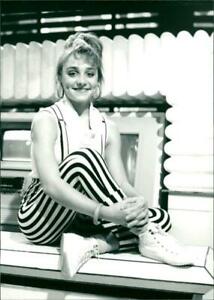

Two BMs over I met Sally Dewhurst, one of the actor-dancers who once played Rumpleteaser in Cats and whose characters now help transform the Cirque du Soleil’s many “acts” into one integrated story. Her decision to join up may have been influenced by her Londoner vaudeville trouper parents—mom an opera singer/acrobat and dad a tightrope walker “I’ve got a picture taken when I was 18 months old,” she smiles, “when he took me up on the wire! He’s still at it now at the age of 58, though he now has to use anti-inflammatories.”

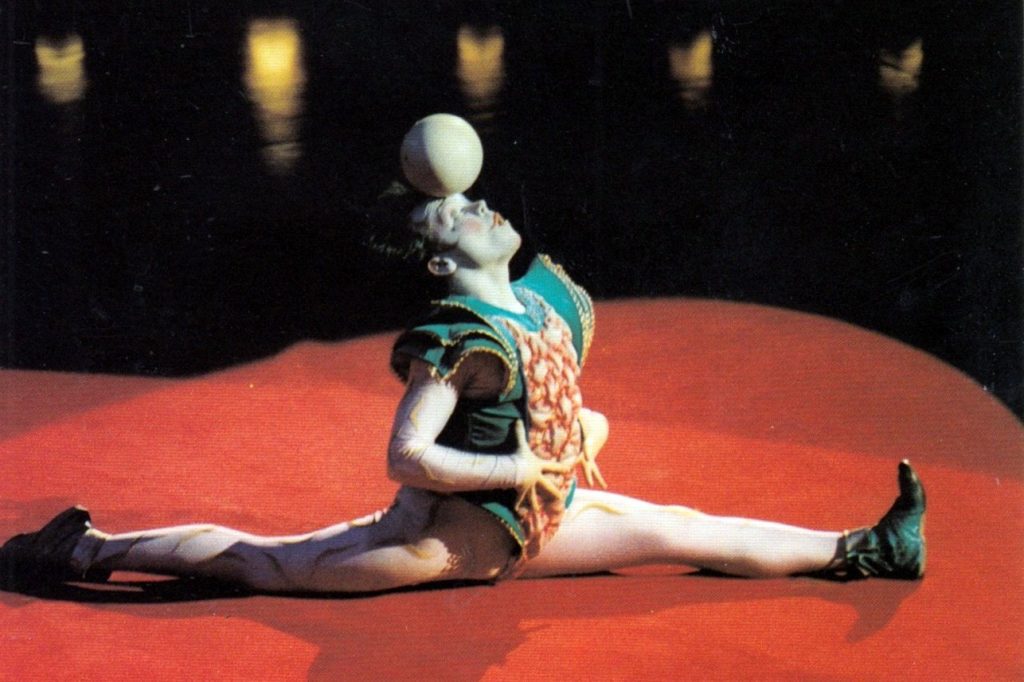

The juggler I met wasn’t born out of a circus family’s trunk. Frederic Zipperlin is stage-named Boul, French for “ball”. “It’s a good name for a jongleur, non?” It was only recently, between the ages of 15 and 17 that he completed a new circus diploma program in Paris: artistic skills each morning; technical skills like circus carpentry, math and French in the afternoons. Yet Frederic had to teach himself his own remarkable specialty—mouth juggling. And he still has to practice every day, as does everyone who works under the lights of the ring.

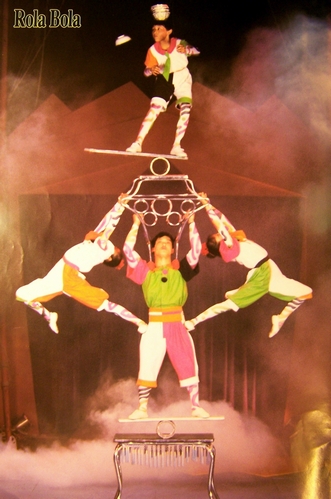

Across from the “baise-mobiles” is the regular camper-trailer for a crew of Chinese children, four performers aged 14 to 17, stars of the Rola-Bola balancing act from Shandong, Peoples’ Republic of China. They spend time off during the day making a few purchases in Chinatown– as well as some long beans, a Sports Walkman and tapes of Chinese Opera from Taiwan and Hong Kong. They are accompanied by their teacher and government translator, who makes sure all questions concern the circus only. The group is now six months into a ten-month contract and all is okay at home, but everyone is homesick. It was a short interview.

There are two other young performers, Marie-Eve Dumais and Amelie Major (ages 15 and 16) who perform on what is called a Barre Russe with the help of two strongmen who hoist up this balance bar. They don’t have their own tutor, but join the other children of the crew in the required half-day of school classes. “What’s the hardest part for you?” I ask in English. “When you are alone. Everyone accepts you, but they are all in their little groups. After the show, at night, that’s when I miss my parents.”

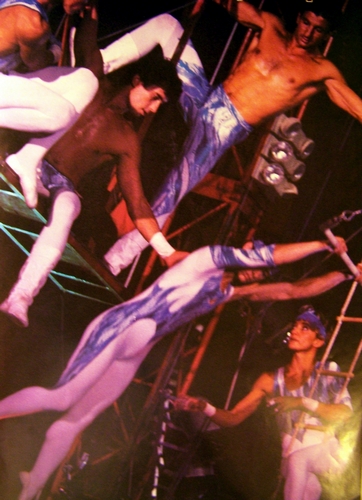

Perhaps the most satisfying arrival story belongs to Stéphane Mayrand, who found his way to be a circus roustabout via his childhood in a rough part of Montreal. “One day,” he delightfully explains in his medieval-tinged Quebecois accent, “my father took me onto a boat and told me ‘This is where you are working for the summer’. It was the best thing he ever did, taking me away from the gang I grew up with, surrounded by refineries, pool halls and ‘bowlings’—not one theater or cinema, no library. At the end of that summer they gave me the money I’d saved up. It was enough to get away from home. I went to Europe, where I met travelers from all over.

“So basically it was seaman’s work that brought me into the circus, because when you are out to sea you have to know all kinds of ropes and splices and rigging. When I met a girl who was learning trapeze and wanted one of her own, I told her I could make it for her. Soon I started going to trapeze school too, and after a year they asked me to join the company as a performer as well as doing all their rigging.” After a bad arm injury, Stéphane had to quit performing. “But when I first arrived the tech director saw my interest and got me to work immediately, rigging the Big Top.”

And that’s where we were, along with Stéphane Pilon who also worked for the Tentmaster, at the base of the giant. They asked me if I was afraid of heights?

“Yes,” I respond without hesitation.

“Well, would you like to go up onto the Big Top?”

“Yes,” I hear myself repeat, before my gullet can rise into my mouth.

“Here is a rope you can hold on to,” offers one of the two Stéphanes as I followed his heels up a ladder. The other Stéphane checks my soles for pebbles and then, before I could think, my sneakers join theirs bounding step by step on the roof of that rubber behemoth. It is like stepping out onto a trampoline set at a 45-degree angle, then climbing even higher on rippling waves up to its zenith. At the very top is an opening, where I could hang on and peer down into the tent, down through the rigging where the French and Algerian male and female trapeze artists rehearsing near the top will soon stop each other from falling what seems like hundreds of feet to the ring below. It is somewhat less in fact, which I find difficult to believe from where I stand, or rather crouch, on this blue and yellow sea with the San Francisco skyline at eye level all around.

There is little real danger of the tent falling. Wind, however, is what the circus techs actually do worry about. “During the montage we always check where the wind comes from and put that side up first. If the tent is up and then fills with wind that can’t escape, it can explode outward. So we are more afraid of it flying up than falling down.”

I thank the two guys for their care and congratulate them on their skill. Then we start down. “You can let go of the rope for a while, if you want.” And for a few scary paces I just feel my way on the spring of the tarp slope without any anchor. “Come back tomorrow, we’re washing the Big Top from up here,” one offers. Isn’t that dangerous? “Slippery as glass. But there’s a rope you carabiner onto.” Great, I nod. But once was about enough. Thanks!

Back on terre firma the first soul I encounter is Jacynthe Normandeau, hurrying to get into makeup—old-folk wrinkles and besparkled eyes– for that afternoon’s show. “I’m Meme! The old lady who’s really alive, who still wants to have fun. She has a bit of Alzheimer’s but still can do ze Twist!”

Audience members are already entering the Big Top, and I join them. Benny Legrand is clown-harassing some of them; he has already found the fool who gives up his tie. Special colored fog effects envelop huge areas of the audience, and out of it zany characters emerge, including an old woman announcing, “I just want to have fun!” The circus band begins to sound. A large business-suited man is handed a top hat and becomes the Ringmaster.

It has begun again. And knowing how it works does not diminish its magic by even one tittle or a jot. To wax a bit poetic, the circus ring that once arrived on horses and elephants still continues to show up for those who need it; a circle we enter into willingly until we have to leave. But not before the pratfalls of its clowns carry us down in the sawdust and those perfect death-defying feats of derring-do let us too soar into the thin air.

As for what it would be like to run away and join I found, among the staff and the techs as much as amid the performers, people who were just as pleased to be there as the audience.

“We’re still passing the hat,” Benny tells me, “and validating the lowly art of busking, only now it’s to a crowd with disposable income. I can still remember one mud show—you know, tent up in the morning, tent down at night—when I was in front of my car mirror with a flashlight in the rain, taking off my make-up. Now the quality of life for performers if far greater, and if it takes oil company money to do it, we’ll take all we can get. The people living in these trailers have eaten our share of Kraft dinners. And we’re not arrogant enough to think that it’s not waiting just around the corner the moment we are out of here.”

Running away to the circus would be hard work, eleven shows a week, ten months a year. “The public leaves the tent really excited. But we get out of here each night quite tired, or even depressed,” is how Stéphane the muscular ex-trapezist puts it. “But the acclaim helps a lot.”

This is an “orphaned” piece of writing, in that it never ran; I do not know why. You’d have to ask Kim Corsaro, editor of the SF paper that became Bay Times. We never spoke after that.

If it had been printed, my endnote from those early days when Cirque shows opened in only one city at a time (and not multiply in Vegas) would have read:

Cirque du Soleil’s entirely new show premieres on July 12 at their usual 4th and King Street site in San Francisco, then goes on to San Jose on August 25. Wait until their box office opens next to the blue and yellow Grand Chapiteau in Mission Bay to save yourself Bass’s [now Ticketmasters’] so-called “convenience fee”.