Mark Freeman, originally published August, 1988 in Coming Up! (now Bay Times). Revised December 2014

INVOCATIONS

“I can’t bear to be losing you, ‘cause I’ve loved you my whole life through. Somebody shake me, wake me, when it’s over.”

“Now if you feel that you can’t go on, because all of your hope is gone, and your life is filled with much confusion until happiness is just an illusion, and your world around is crumbling down, Darling reach out. Reach out to me.” Holland, Dozier & Holland, for The Four Tops

“Hitsville USA, shrine to Motown music: the mothiest scumbag place I ever played. But the audience there, bless their hearts, made me feel at home.” Michelle Shocked, musician

Into The Motor City

Downtown Detroit has survived some hard times. It is still in them, so promises to be a place that lives up to a bad rep. But it also has a strong heart.

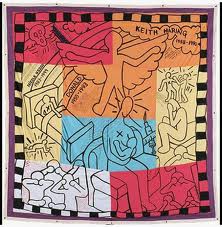

By putting Detroit on its tour, The Names Project included a city whose gay agencies began to address the AIDS crisis about five years ago, and whose Black mayor has been somewhat quiet on the issue, (to keep closet doors from banging, say a few). With an 86% Black population, inner city Detroit’s PWAs (People with AIDS) are most likely to be folks of color, or intravenous drug users (IVDUs), or female partners and their children—the “second wave” of AIDS. It also has its share of familes and friends of those who left there to live (and die) in the more tolerant cities of both Coasts.

Early on the Fourth of July, 1988 I leave the airport in San Francisco; at the same time a six-wheeler heads out from New York, transporting the Quilt ahead to the 16th out of 20 cities on its tour, before it will return to Washington DC in October.

This truck carries a nomadic cathedral, a living memorial that comes for only a few days. It is more like an Ark of the Covenant than any marble monument. In kinship with Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial it is also made simply of names. But unlike any official effort, the Quilt is crafted piece by piece by friends and folks.

This diary of a week spent with the Quilt in Detroit is a patchwork of names and naming, and I have taken the liberty of adding some songs, rituals of birth and life, prayers of death and memory. But to protect from reprisals and discrimination, even toward surviving family members, real names are not used here. PWAs chose their own pseudonyms—perhaps the name of a childhood hero or of a remembered friend.

These pieces of stories offered me a momentary chance to get away, from my own city’s fish-eye view of the epidemic, and to see how another place is doing. Here is what I find during a week in Detroit.

*****

There’s a pulsing heat rising over Woodward Avenue, Detroit’s north-south artery. Trees still show green on this lick of land off Lake St. Clair, between the Great Lakes of Huron and Erie. But down on the ground the grass everywhere is burnt by a drought that has all of the Midwest by the short hairs. Above the freeways, the giant green computer signs read: “Let It Rain! Let It Rain! Let It Rain!”

It’s summer in the city and everywhere there are teenagers in jams of all colors, or cool matching outfits. An amazing sound system on some kid’s scooter shakes a whole block of Six-Mile with hip hop; some are unison dancing on the street, others are sounding off, walking in single file and finger-popping like crazy mixed-up Marines. How can anyone here be thinking about a health crisis?

Up the Street from Cobo Hall

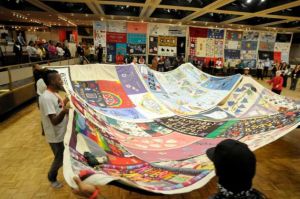

Cobo Hall, the Quilt’s local home, sits at the foot of Woodward, on the waterfront right next to Joe Louis Arena (which proudly displays two bronze statues of the Brown Bomber himself, one simply of his forearm-and-fist. The day before the Quilt opens, volunteers are taught the choreography of “unfolding,” though they are yet unaware of what the whole event will look, or feel, like.

“It’s gonna be hard work,” says Areena. She is part of a local program of Black high school Peer Counselors whose job is to reach out to teen parents. They’ve come as a group to volunteer at Cobo Hall.

During the rehearsal, Areena wanders to the front of the hall and there spots one of the forty new Detroit panels mounted behind the state. She breaks into tears.

“When I saw his name, I broke down,” she says. “He went to my church, he was a dear friend of the family. I knew he had AIDS, but not until two days before he died. I knew he was gay, it was obvious; he never said flat out, but it showed in everything he did—how he’d mention his boyfriend, the way he talked, everything. I would have wanted to see him before he died; but not the suffering in his eyes. Then, I saw the panel; I needed to see it, cause I didn’t cry before.” Welcome to the Quilt.

The teams of “Unfolders”, among them Areena’s, learn to fulfill their ritual duties with grace. As the name of each of the dead is read aloud, each square, made of eight panels the size of tatami mats, the size of human bodies, is opened petal by petal. It billows in the wind like a floating lotus, then settles in place. The last square to open, in each city of the tour, is a yellow one left blank for visitors to add their comments. Later, another of the peer counselors would get on his knees on the open Detroit square and write this:

What AIDS is NOT

It is not God’s punishment for humanity. It is not just a homosexual disease. It is not anyone’s fault. It is a disease. It is something we must learn to deal with compassion and understanding. It is a disease like a cold or a flu, but it kills. We must be careful. Peace. 2000 for a New Age.

And On the Street

At mid-day, waiting for a bus on Woodward, I overhear two street people arguing about the amount of change they’d need to board. One of them, wearing a sooty grimy camouflage jacket (even in 100-degree weather), has sallow skin and pupils constricted from being narcotic sick, or worse. He almost-hisses at his buddy the familiar expletive “Bitch!” in a lispy tone. I smile slightly in, recognition, and he sees me.

People on the bus try to ignore him as he walks down the aisle broadcasting his louder-than-necessary repetitions to no one in particular. “This heat is frying my brain! My fuckin’ brain! I’m not polluted—the air’s fuckin’ polluted!” When he sits right behind me, I tell him I agree with his comments on the weather, and he starts to talk.

He grew up all over, a military brat. He calls himself Doc. He was a medic in Vietnam. He stays loud and agitated, until I mention I am in town for the AIDS Quilt. Then he calms down, his voice lowering to a level meant only for me to hear. I ask him what he thinks it would be like to have AIDS in Detroit, does he know anyone?

“It’s OK. Yeah. There’s less discrimination here than in a small town. In a city everybody has their own problems, they’re more likely to leave you alone. Two friends of mine died. But it was in a hospice, a good place. They had family there, loved ones all around them. They weren’t ‘institutionalized.’ That’s the most important thing, isn’t it? To not be alone at the end.”

Before he gets off at his bus stop, Doc gives me detailed directions on how to recognize my stop, so I won’t miss it. I’m touched that he is concerned about my safety.

Southwest U.S.

“May your road be fulfilled, Reaching to the road of your sun father. When your road is fulfilled, In your thoughts may we live. May we be the ones whom your thoughts will embrace. On this, on this day, to our sun father we offer prayer meal. To this end: may you help us all to finish our roads.”

Zuni Prayer, Presenting an Infant to the Sun

*****

Babylonia-Sumeria

“Oh Gilgamesh, why does thou run in all directs? The life thou seekest thou shall never find. When the gods created man they gave him death. Life they kept in their own hands.”

–Epic of Gilgamesh

Sharing the Loss: Two Families

There is an AIDS bereavement group in Detroit, a support system for counseling family members. The group’s therapist at the Center for Attitudinal Health tells me: “There’s so much growth that you find in this work. I’ve also had to deal with my own illness. Nothing terminal (it is multiple sclerosis), but you do learn how to stop being a victim.” She puts me in contact with two women in the group. Sally’s mother lost her son and divorced her husband at the same time, two years ago. “When I was going through it, I had nobody, nobody at all. My family, my mother, my brothers, they all knew he was gay for the last ten years, and they knew what he had. But after he’s gone, you just can’t talk about it.”

She’s getting the afternoon off from work to go see the Quilt. Her boss understands. “He’s a nice young man, married.” At first she told him Ty had cancer, so she could borrow some money from the company, but felt so guilty, she had to go back the next day and tell him the truth. So many other people at work you can’t tell, of course, we even still have people there who are against ‘coloreds’!”

I spent six weeks in the hospital with Ty, and I can’t tell you how many boys died without their parents. I held four of their hands while they died. And I have three right now that I still write to. They just don’t have anybody. The last thing Ty talked about was how he wanted me to get involved in AIDS work. But aside from those boys, I haven’t.

“I wanted to bring him home, but there was no room. I wanted to bury him in Detroit, but back then there were few funeral homes who would deal with AIDS.” At Cobo Hall, she discovers that some unknown person in another city has made a quilt panel for her son. Awash in sobs and laughter, she ushers me over, to show me where her son is.

“To realize that there is really that much love out there in the world. Every parent should see this. You would have to know, whoever made Ty’s, knew him. See how tasteful his name is. He never liked anything garish. It’s just like him. And the material it’s on—that was his bathrobe. I had no idea this would be like this. But it’s sad, too, of course. So many young people.”

The other group member described her family, and its response, differently. “We’ll never be the same again. I’d say we’ve changed for the better. We drew closer and worked together as I never felt we could.

“ My nephew Ray died almost a year ago. At first, when we heard about making a panel, we wondered, ’Is this hokey– or what?’ Then, “’What do you put on it?’ Then, ‘Can we do it?’ Last Thursday we saw an article in the paper and finally decided. So we spent the Fourth of July weekend sewing it as a family.

“He loved spending time outdoors in the woods, even after his diagnosis. And we had a picture of him wearing this t-shirt that has trees and a setting sun over a lake, reflecting in the water, and an eagle rising. That had to be it. ’This is so lovely,’ someone said, ‘I wish Ray could see it,’ and then we realized: of course he’s seen it—it was hisfavorite t-shirt!

“He and his Aunt Betty were more like good friends, close in age (he was 36 when he died) and probably closer than I was with my own brother. Even with her, though, the one area he never talked about was his private life.

“We never really knew about his lifestyle, so we found out about his…’gayness’ along with his diagnosis. We wouldn’t call ourselves fundamentalist, you see, but I suppose other people would. His mother now says that if a person has a sexual preference, they must have been born that way. That’s not how she used to think. But people saw him as the most caring, generous person in the family; even if everyone else forgot Mother’s Day flowers, they came from him. And I think he was afraid of losing that positive image.

“He was probably being rational, not wanting to tell people. Where he was living, he worked for a family construction firm, as a trusted person who could do anything, ten or eleven hours a day, six or seven days a week. When they found out he had PCP [pneumocystis carinii pneumonia], he no longer had a job. That was when he came back to us. It happened again here, once. It was his best friend in this small Lutheran town in the Upper Peninsula where our family comes from. It’s real traditional. Right-wingers. And this one friend couldn’t handle it and was very threatened by it, I don’t know why; that was a real hurt for Ray.

“But when his other friends in the town heard about it, they were furious with this guy. And of the family members–we’re talking about 30 or 40 people, only one sister-in-law was afraid, but she’s always been a bit strange. Everyone else, maybe they were a little surprised, but they were supportive. His two great aunts, 65 and 72 years old, hopped into their little DeSoto and drove 600 miles to see him when they heard about his diagnosis. His daily care was mostly by his brother, a brother-in-law who came over and shaved him every day, his parents, a few aunts; we wanted to hover and mother.

“His father was in the building trades, a big sturdy man who never showed feelings. It was a big shock to Ray to learn that his father had cried on hearing the news. He had just retired himself, and so flew to his son and spent six or seven weeks there, then brought him up here to Detroit, stayed with him virtually every day of his life. His dad learned how to regulate the IV and hang bottles of DHPG for CMV [Cytomegalovirus] that kept Ray from going blind in his ri eye—he’d lost the use of his right already.”

Ray’s father had cancer during those last months, but didn’t know it. He didn’t have time to think about his physical pain. “Now,” says Betty, “he may be looking at his own death, and he’s become closer to people. Scandinavian and German people tend to be more coolish, not a lot of touchy-feely. But over the past year, we’ve probably hugged and touched and said, ‘I love you’ more than we ever had in our entire lives.

“Ray gave us the opportunity to talk. Though it’s painful to talk about, he was able to help people feel comfortable. His older brother and dad are up now in the hometown. He brought two horses with him when he moved back, and they are being taken care of up there as if they were his own kids.

“It’s almost like I’m afraid to go see the Quilt,” she concluded. “Everyone came over here to see the panel, but I guess that is still within the family, sort of private. His mom is still trying to decide whether or not to list his last name when we turn in the panel.” It is a major decision for families brought up to keep private things private.

When the family finally brings their panel in to Cobo Hall, they’ve decided to include Ray’s full name, so that others can find it. They proudly display their handcraft: a beautiful piece of work, a masterpiece. And their photo shows that Ray, smiling and rugged in his t-shirt, was no less so.

Betty, after seeing the quilt: “It’s not your private sorrow anymore. At the funeral home, well I used to think that was barbarous. But here, all this sharing, tears, it’s been a good thing. You don’t feel like you’re hiding anymore. We share this loss. Eveyone is sharing in something bigger. It’s the whole world.”

Coptic Text

“It is said: This heaven shall pass away And the one above it shall pass away, For the dead are not alive and the light Will not die.” –The Gospel According to Thomas

The Three Musketeers

This city has more than its share of women infected with the AIDS virus. Several were willing to talk about it. One styles herself Jenna: “If I’d had a little girl, I’d have named her that.

“There are three of us who are friends. The Three Musketeers we call ourselves. You know, I’d never experienced that before, to be part of a group. I’d always been a loner. Now we three go out, meet twice a month, always get together.

“I’m not sure how I got HIV positive. I was married and he was taking all kinds of drugs. I don’t know which. My current boyfriend says he’s negative. He is a female impersonator, though. Guess where he is right now? He just called and says he has a job at a private party—at Aretha’s!! Can you believe it?

“Anyway, what does it matter how I got it? What can I do now, except safe sex. And I am very active, but it’s always safe and just with this one person. I did stop for a while. After a month of total depression, I started taking care of myself. Found the support group, got a bike, joined an exercise club. Lost 36 pounds. Like I say, the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Jenna explains that the next Musketeer would rather not talk. First, she’s angry. “Just angry, period. Also, she moved to a new city and took a job where she talks on panels about AIDS every day. It’s good, I guess, because there’s not that many Black folks willing to talk about it. But she gets tired of it.”

The third and last Musketeer calls herself Faith, “cause I have lots of that.” She is also on anti-depressants to help deal with her diagnosis and its complications, and with her two boys, ages 6 and 8.

“To everybody here, you have the Plague. See, I had a substance abuse problem. Alcohol and, well, I threw my back out and an MD prescribed Darvocet, then Percodans. Then my husband and I went on heroin for about a year. Finally I took my kids to a shelter, my husband moved out and I checked into a hospital for 21 days. Now I’m completely clean.”

She and her boyfriend are “very, very cautious. Can I be personal? See, I’ll be giving him head and he’ll say, ‘We don’t need a rubber.’ But I have mouth problems, canker sores, so I say we do. My new invention, though, is going to be mint-flavored nonoxynol 9. We could sell millions and be rich. More people would be giving head than ever. Strawberry. Evergreen. Girls wouldn’t mind, guys would be happy! Don’t steal this idea, now!

“Actually, he started out as a trick, which is how I met a clean guy, supporting my habit.” Her kids, she says, will eventually go to her brother and his new wife. “I love her. They’re into everything I am, except that I’m a Christian and they’re atheists; but that’s okay.”

Faith is in AA and the kids are in Ala-Tot. She tells about the 12 Step Program’s children’s books, in which Pepper the Dog’s mother keeps getting so upset and sleeps all day and forget to take him on walks. So he thinks he must have done something wrong. Until he talks to his cat friend… “They get it. They also know about AIDS. I showed them that video about Susie, that followed a woman with AIDS from day to day to the end. She died, and her baby and husband carried on, but it was beautiful, because they did it the way she wanted.

“When it was over, the 8-year old asked me, ‘Are you going to die?’ and I told him, yes, everybody dies, but we never know when. It could be tomorrow or a long, long time.” She has to figure out how to give them just enough information to satisfy them. “When they’re ready for the next step, I’ll give them more.

“I’ll tell you. This disease, either you get your shit together or you die. Sometimes you die even if you get your shit together. I look at it as a warning. You better enjoy your life, living and safe, while you have it.”

On the first day of the Quilt: “It’s devastating. I don’t want my kids to come here and see me. I guess I want them to say, somehow, ‘We finally got rid of her at 90! Funny how she thought she’d die at 30, but she sure held on.’ It’s hard, you see all the survivors who are suffering just as badly as those with the disease. I can handle my pain,” Faith asserts. ”It’s what happens to everyone else.”

Mythology teaches that our job here on earth is to participate joyfully in the sorrows of the world.” –Joseph Campbell

And a Handful of Other Warriors

Like elsewhere in this country, the first and foremost to do battle with the epidemic in Detroit were gay males. Wellness Network is still predominantly white and gay, but is now considerably more colorful, largely through the offices of a Black volunteer director. Wellness House Michigan is a live-in hospice working in coalition with organizations like Visiting Nurse Association and Black Family Development to coordinate care to a wide range of clients.

Women, as across the country, predominate in the next lines of support: lesbians; medical and nursing people and social service workers who see the ravages firsthand. Some minority organizations and religious groups have also found their way toward the front.

The real enemy, whether among homosexual or ethnic groups, continues to be Shame. Along with Fear and Stigma. A handful of embattled activists in each of these communities tries to reverse this reality. Here are what some of them have to say.

“Among PWAs, about 75% have ocular complications, and 20% of those go blind from CMV, the virus. We’re encountering some racism and homophobia among the profession. So it is not an unusual response to put people somewhere on a waiting list and hope they die before you have to provide service.” –Professional Rehab Counselor

“It’s easier for the homosexual community. People care about them. Nobody cares about drug users from the Black community. IVDUs [now IDUs for Injection Drug Users] are categorized, stigmatized, abused…. One doctor convinced a father to talk frankly. It turned into some sensationalist commercial. The ad agency wrote lines for him to read in a script: ‘I killed my daughter. I killed my wife. I don’t want to kill anyone else.’ Of course, he refused.” -–Community Health Awareness Group

“There is no end of horror stories about families of kids with AIDS. We know of three cases where a mother and her infant had to be separated before the bureaucracy would consider caring for the child under its ‘abandonment’ provision. One family’s friend of 27 years turned them in as a threat to the community. A foster mother’s family threatened to never let her see her own grandkids again if she went public in any way…. About 75-80% of pediatric AIDS cases here are Black and Hispanic kids. The number one problem is prejudice—not just racial, but also economic and religious differences. Before speaking to a Catholic agency I actually had a representative whisper in my ear, ‘Abstinence! Don’t mention condoms!’” –Children’s Immune Disorder

“We’re fighting to keep kids together with their mothers and at home. There’s a so-called ‘moral’ impetus to take the kids away. It’s not easy, like when the mother has to giver her kid AZT every four hours, all night, and the mother is usually sick. We teach them tricks: filling the night syringes before you go to sleep so you can just roll over and pop one in their mouth.” –Renaissance Home Health Care Nurses

“What is sad, particularly with gays within the Black community, is that if ever there was a time in history to come together, this is it. Instead it’s hush-hush. Detroit is staunchly Baptist. Some of these preachers have to start endorsing compassion. And the schools. The City Fathers have been dancing with economic ‘revitalization’ of the city, at the expense of realizing that a large segment of the population, and that means Black people, are in grave, grave danger.” — Black Male Intellectual and Writer

East Africa

And when they name you, great warrior, then will my eyes be wet with remembering. And how shall we name you, little warrior?… Must we call you ‘Insolence’ or ‘Worthless One’? Shall you be named, like a child of ill fortune, after the dung of cattle? Our gods need no cheating, my child: They wish you no ill. They have washed your body and clothed it with beauty. They have set a fire in your eyes… They have given you beauty and strength, child of my heart, And wisdom is already shining in your eyes, and laughter.

–Didinga Naming Song

*****

What Makes a Volunteer?

I ask a group of three “unfolders” what brings them to this work, and all three answer the same: Guido. “He used to cut my hair. I was impressed by his commitment to a cause greater than himself. My commitment has always been to family, but he seemed able to make all these people family.” “Same here. He has the ability to cause people to feel. He begins taking interest in you and it’s contagious. Before you know it, he’s got you under his spell.” “Guido’s my older brother. A lot of his friends are gone. He used to live in San Francisco and I used to go visit him with my wife and baby.”

Guido, it turns out, is the volunteer coordinator for the Detroit Names Project. How does someone become an “inspiration?”

“I was a studio hairdresser, movie studios. So when I moved to San Francisco I was already loaded, had a soon on Union Square near Macy’s in ’74, a house on 16th and Castro. I was shooting speed, speedballing with coke, and was always with boyfriends who were broke. Form there I went downhill to the Tenderloin, the Slot, a sleaze hotel South of Market, and the sex clubs in between. No way I was going to quit there.

“So I moved back here to Detroit to stop. No program. I just quit. But it was during that time that my best friend Jay—we used to have a summer home on Fire Island together during our twenties, see, we were both studio dressers when we were 18, we thought we were the Golden Boys—well, he got sick and died then. In fact, when he died, that’s what he said to me: ‘We lived the Golden Days. Who thought they’d ever end?’

“But these are the Golden Days now, I think. These are the times when gay men can discover the sense of their own worth—all we were doing then was coming out of the closet and being party boys with the sort of ‘movie star quality’ that gay men were supposed to have, dressing well, doing every kind of drug.

“There’s something more, something innate in gay men: a sensitivity of spirt, and I discovered it in myself. I’d never thought it was there. You know, I used to not talk to certain people, if they didn’t ‘walk right.’ Now I spend my mornings putting socks on people who can’t walk at all.

“I know what made be become an AIDS volunteer was missing that time during the last stages of Jay’s illness, due to drugs. Now, I realize that however small the thing is that we for someone, there’s no way to measure it. Taking a guy to the store this morning, no big deal, it was an hour to me. But it was the first time in a a month he’d gotten out, anywhere. It matters.”

Such conversions “on the road to Damascus” can seem unbelievable, or like cloying televangelism, until we know someone like that personally. Seen from one side of the Treatment vs. Transcendence controversy*, this may smack of fatalism, or a tendency to romanticize death in the gay community. But AIDS is not a historical aberration; some such disaster has occurred in every generation. Only since the advent of antibiotics have we somehow convinced ourselves that we are exempt from mortality. People like Guido are not giving in to death, but they have learned that it is impossible to make love to Life without a willingness to embrace its other side.

*During the ‘80s a false dichotomy put ACT UP activism (“Your laws are killing us!”) on one end and Louise Hays’ A Course In Miracles (“You can will yourself well!”) on the other. It might help in the understanding of that division to recall that the successful AIDS meds treatment “cocktail” was still nearly seven years in the future at this writing. The only medication then available was AZT alone. About half of those who chose to take it died of its side effects. And among those who refused it, half died of AIDS complications.

Civil War era, United States.

“Come lovely and soothing death, Undulate round the world, serenely arriving, arriving, In the day, in the night, to all, to each, Sooner or later, delicate death.

Praise be the fathomless universe, For life and joy, and for objects and knowledge curious, And for love, sweet love—but praise! praise! praise! For the sure-enwinding arms of cool-enfolding death.”

Walt Whitman, When Lilacs Last In the Dooryard Bloom’d

The Streets, the Women & Children

The picture painted for me by this Infectious disease nurse is so bad it is hard to believe. “We have a 25-year old IVDU, probable ex-prostitute. She’s down to 95 pounds and hanging, literally, on her crutches. She couldn’t eat because her mouth sores [thrush] were so bad; she couldn’t sit because of her herpes. She sends her girl, a four-year old, two blocks away to a soup kitchen; the kid brings them back food.”

Another of the handful of nurses helping the worst-off make their way through a callous bureaucracy, takes me to see. The streets of Mack Corridor are potholed, most of the houses are boarded up, some with official red notices tacked to the door. More than not are empty, maybe from fires as far back as the Detroit Race Riots of 1967. Or else their owners just got sick of the neighborhood. This wood-framed one is a drug house.

You can tell, not because it is any more or less ramshackle than the others, but by the 11-year old sitting on the stoop all afternoon. He’s skinny, with the torso and long legs of a running gazelle, but his boy is not a runner. He is a spotter, old enough to watch the street for outsiders, and to be paid in crack or dollars.

He has instructions not to let anyone in, not even the tall blond nurse standing out on the sidewalk. But he knows her and sends a message upstairs for her patients to come down; a slim woman on crutches, KS bumps all over her face, and a little girl, cute as a proverbial bug, with corn-rowed hair and a cough.

“The mother is much better,” explains the nurse, “compared to a month ago when she was pointed out to us by her sister who is alienated from her but did care enough to get some medical care. This woman hasn’t let anybody touch her in over a year. We have found that’s a crucial thing, getting the first barrier down. She’s doing so well now; her doctor said it wasn’t the AZT: ‘It’s too early.’ Only one week. It’s the care and concern and knowing that someone is paying attention to her.

“Call me Champagne,” said another woman, kids running in and out of the scantily furnished but very clean living room of a brick house not far from 6-Mile and Woodward. “I used to carry money belts on airplanes, my boyfriend got me a stage passport. And I saw a lot of entertainment people come in to buy drugs; that was before I was shooting. We didn’t know anything about Crack, only Raw—heroin to sniff. It’s like different people. Heroin addicts’ bodies get all marked up, they get diseases. Still they take only so much, to stop being sick. But a crackhead, their mind is gone, baby. They do it all day and night, never get enough. Non-stop.

“I’ve go six kids but two of them I didn’t raise. Their grandmother did, upstairs. What’s important to me is that I stay healthy enough to take care of my babies.”

Like her, two of the kids are infected with the HIV virus; and the four-year old shows symptoms. “At first they thought he was retarded; he wouldn’t talk and walked with a limp. Then they found an ear infection== his balance was knocked off. By then they had taken my kids away, and his foster parents said he wouldn’t eat. Partly it was sickness, but party he was withdrawn because he was 16 months old and he’d never been away from me before.

“The boy was finally examined and diagnosed. The foster parent heard the word AIDS, she was real religious and had other foster children, so when she found out, I got my boy back. Two months later, I got the other kids back, too. He’s four years old now, and taking AZT, but none of us has ever been hospitalized. The baby (who also tested positive) is 15 months old and she seems to be doing fine, even in this heat wave.” Her daughter’s long dark hair is blowing in the fan’s draft as she tilts her head back toward it, smiling.

“I’m a pretty private person, that’s why I haven’t’ got into a support system. But my family knows. My son’s pre-school teacher knows. My grandmother, she definitely knows but may not really understand. She is a trip—a retired factory worker, Chrysler. What you call a beer drunk. She talks about people all day, me included. But if I need her, my grandmother is in my corner.

“She’s the one who called those people and told them I had abandoned my children for a month. That’s what made me stop using drugs. They took my babies away. When my boy got home from the hospital, he was so puny and looked so pitiful and I felt so guilty—that’s when I stopped for good.“

Champagne says nobody is willing to admit they have AIDS because so many people think you can touch somebody and get it, “but I’m too wrapped up in my own situation to do anything for anyone else. My kids have got nobody but me. This girl is how I’m keeping my sanity, she keeps me from falling apart.”

A Puerto Rican woman can’t think of a name to give herself, no hero or role model, but says she wants it to be Spanish. I’ll call her Lola, as in Damn Yankees.

“They say I’ve had the virus for eight years, but I don’t know. I was always shooting up; I was so fallen down I wouldn’t know anything from then. I first noticed, after I was in prison for a year, getting tired for no reason. I wasn’t doing drugs there.

“Every time I feel like shooting up now, I go to Vida Latina [the primary agency serving Hispanics]. Because all your friends are dope fiends, so there’s no place to run to, especially for us Latinas. ‘La Casa’ is a good place, but I don’t know if half of them really understand us. We’re liars. We’re cheaters. We say we’re clean, anything. We’re scared to trust anyone.

“But, you know, if I need help and I go to an addict, he’ll help me faster than a straight person would. All the junkies I know are willing to share; if nothing else, experiences. Even the ones whose tests came back negative. We’ve sat in my house and cried together. All we know is street shit, and there’s nothing to teach you about AIDS out there. One girl said, ‘I hear you got AIDS’ and I said yeah. Why not. I told her—my throat hurts, my lungs hurt, a pimple lasts a month. And there’s nowhere to run to at three in the morning.

“I’ve always made my money by cashing checks or boosting [thievery], since I was little. My father was a drug addict. I learned to dress up, I’d look like Marilyn Monroe, different wigs. I’m a booster; it doesn’t matter if they’ve got a chain on something, I find a way.

“There’s only one thing I can say I’m proud of. I’ve never given my kids away. People talk about us like we’re dogs. People say drug addicts don’t care about their kids, but they’re wrong. I have a daughter, 16, that’s been staying with me. ‘You’re my mother,’ she says, ‘I don’t care what you have.’ Last week I took my daughter and two of her girlfriends, whose mother is a drug addict like I am, to Bell Isle [Amusement Park]. It was the first time I’ve enjoyed myself in 14 years. I see now what’s important. And I heard one of them say, ‘I wish my mom did half the things for us your mom is doing now.’ We’re getting close, only at the end.

“But my two boys have already got [dealer-style] beepers. My oldest, I can see the anger and the hurt in his eyes, like, ‘Don’t feel sorry for yourself for having AIDS, you did it.’ He hates me. He was accepted into college. But instead it’s fast money, fast life. I think my kids are going through this because of me.”

Lola finishes: “I want to tell people, even if they have the virus, they still have a chance. Don’t share needles. Don’t just fuck with anybody without telling them. Tell them. I feel that people with the sickness are the only ones that understand.”

Detroit Comes to the Quilt

It’s hard to imagine that the Names Project began little more than a year ago, with a meeting of eight people. It was a local response, recalling traditional family quilts stitched by loving hands. Its effect has now spread across a continent. It is an unusual message, here in death-avoiding America. And a deeply religious message, one found in the rites and rituals of every ancient culture: that a deep, soothing truth can be found in the midst of pain; that of a victory of love and pride over shame and fear. The Names Project Quilt may just have created the perfect modern manifestation for this tribal truth, and sent out an unlikely group of evangelists to share it. But rather than staying, relatively safely, in the gay ghetto of San Francisco, these evangelicals departed our left-coast Jerusalem for more hellenistic places, such as Phoenix and Detroit.

“I thought we weren’t going to have anyone here,” admitted Jack Caster, the tour manager who used to live in Detroit. “But there are a lot of families coming. Old people. Kids, groups of teens. And more Black people than in any other city except Baltimore, where their Black mayor came and read names.”

The cities in the South, Southwest and Midwest are facing farm crises, new unemployment, old divisions. They are places where sex, though practiced no less, is kept decidedly quieter. News of a “homosexual disease” may come, and be received accordingly. But when the reality arrives, it is too late to blame anyone. These are one’s own husbands, wives, children and parents. By naming, and thereby honoring each one as a person that belongs to us, the Quilt facilitates such awareness.

What places like Detroit, or mid-sized cities in the heartland, can teach about how to deal with some new realities may lead the way for the rest of country in confronting the “next wave” of this crisis. The Quilt directly reached 8-10,000 Michiganders, even bringing in many from the suburbs who “hadn’t been downtown in years,” and raising some $15,000 for local AIDS service agencies.

“It’s a gritty old town,” says the dynamo Infectious Disease nurse who drove through a bombed-out zone within sight of the glittering new Renaissance Center and a multi[million dollar medical complex. “But it’s a good old town. People here, by and by, don’t live lightly; they’re driven. If you work for an auto company you work your average of 60, 80 hours a week. What happens if you’re laid off? If you live down here, you’re scrambling to survive.

“If you drive these streets early in the morning, you’ll see people lifting up the boards over windows and slipping out of all these brick buildings. It’s like a Hooverville. Or the Warsaw Ghetto. But the vegetables from that garden there will be sold in that empty lot over there, come August. It’s like a victory garden.

“Same with the families we see. Most of them demonstrate an enormous wellspring of loving and charity and grace and tremendous courage they never knew they had in them. The stigma is still there—people forced to live in the basement, or denied participation in holiday dinners. But with many others, AIDS really acts as the impetus to draw the family together. They realize that they have to set things aside—judgments about IV drug use, fear of the disease, homophobia—because truly they need each other.

Misheberach (Prayer for the Ill)

May the one who blessed our ancestors, Sarah and Abraham, Rebecca and Isaac, Leah, Rachel and Jacob, bless _____________, along with all the ill amongst us, and all who are touched by AIDS and other life-threatening diseases. Grant insight to those who bring healing, courage and faith to those who are sick, love and strength to us and all who love them. Merciful Parent, let your spirit rest upon all who ill and comfort them. May they and we soon know a time of complete healing, a healing of the body and a healing of the spirit, and let us say: Amen.

–from the prayerbook of Congregation Sha’ar Zahav, San Francisco